Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive Therapy

First developed in 1938, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for years had a poor reputation with many negative depictions in popular culture. However, the procedure has improved significantly since its initial use and is safe and effective. People who undergo ECT do not feel any pain or discomfort during the procedure.

ECT is usually considered only after a patient's illness has not improved after other treatment options, such as antidepressant medication or psychotherapy, are tried. It is most often used to treat severe, treatment-resistant depression, but occasionally it is used to treat other mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. It also may be used in life-threatening circumstances, such as when a patient is unable to move or respond to the outside world (e.g., catatonia), is suicidal, or is malnourished as a result of severe depression. One study, the Consortium for Research in ECT study, found an 86 percent remission rate for those with severe major depression. (1) The same study found it to be effective in reducing chances of relapse when the patients underwent follow-up treatments. (2)

How does it work?

Before ECT is administered, a person is sedated with general anesthesia and given a medication called a muscle relaxant to prevent movement during the procedure. An anesthesiologist monitors breathing, heart rate and blood pressure during the entire procedure, which is conducted by a trained physician. Electrodes are placed at precise locations on the head. Through the electrodes, an electric current passes through the brain, causing a seizure that lasts generally less than one minute.

Scientists are unsure how the treatment works to relieve depression, but it appears to produce many changes in the chemistry and functioning of the brain. Because the patient is under anesthesia and has taken a muscle relaxant, the patient's body shows no signs of seizure, nor does he or she feel any pain, other than the discomfort associated with inserting an IV.

Five to ten minutes after the procedure ends, the patient awakens. He or she may feel groggy at first as the anesthesia wears off. But after about an hour, the patient usually is alert and can resume normal activities.

A typical course of ECT is administered about three times a week until the patient's depression lifts (usually within six to 12 treatments). After that, maintenance ECT treatment is sometimes needed to reduce the chance that symptoms will return. ECT maintenance treatment varies depending on the needs of the individual and may range from one session per week to one session every few months. Frequently, a person who underwent ECT will take antidepressant medication or a mood stabilizing medication as well.

What are the side effects?

The most common side effects associated with ECT are headache, upset stomach, and muscle aches. Some people may experience memory problems, especially of memories around the time of the treatment. People may also have trouble remembering information learned shortly after the procedure, but this difficulty usually disappears over the days and weeks following the end of an ECT course. It is possible that a person may have gaps in memory over the weeks during which he or she receives treatment. (3)

Research has found that memory problems seem to be more associated with the traditional type of ECT, called bilateral ECT, in which the electrodes are placed on both sides of the head. Unilateral ECT, in which the electrodes are placed on just one side of the head—typically the right side because it is opposite the brain's learning and memory areas—appears less likely to cause memory problems and therefore is preferred by many doctors. In the past, a "sine wave" was used to administer electricity in a constant, high dose. However, studies have found that a "brief pulse" of electricity administered in several short bursts is less likely to cause memory loss and therefore is most commonly used today. (4)

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

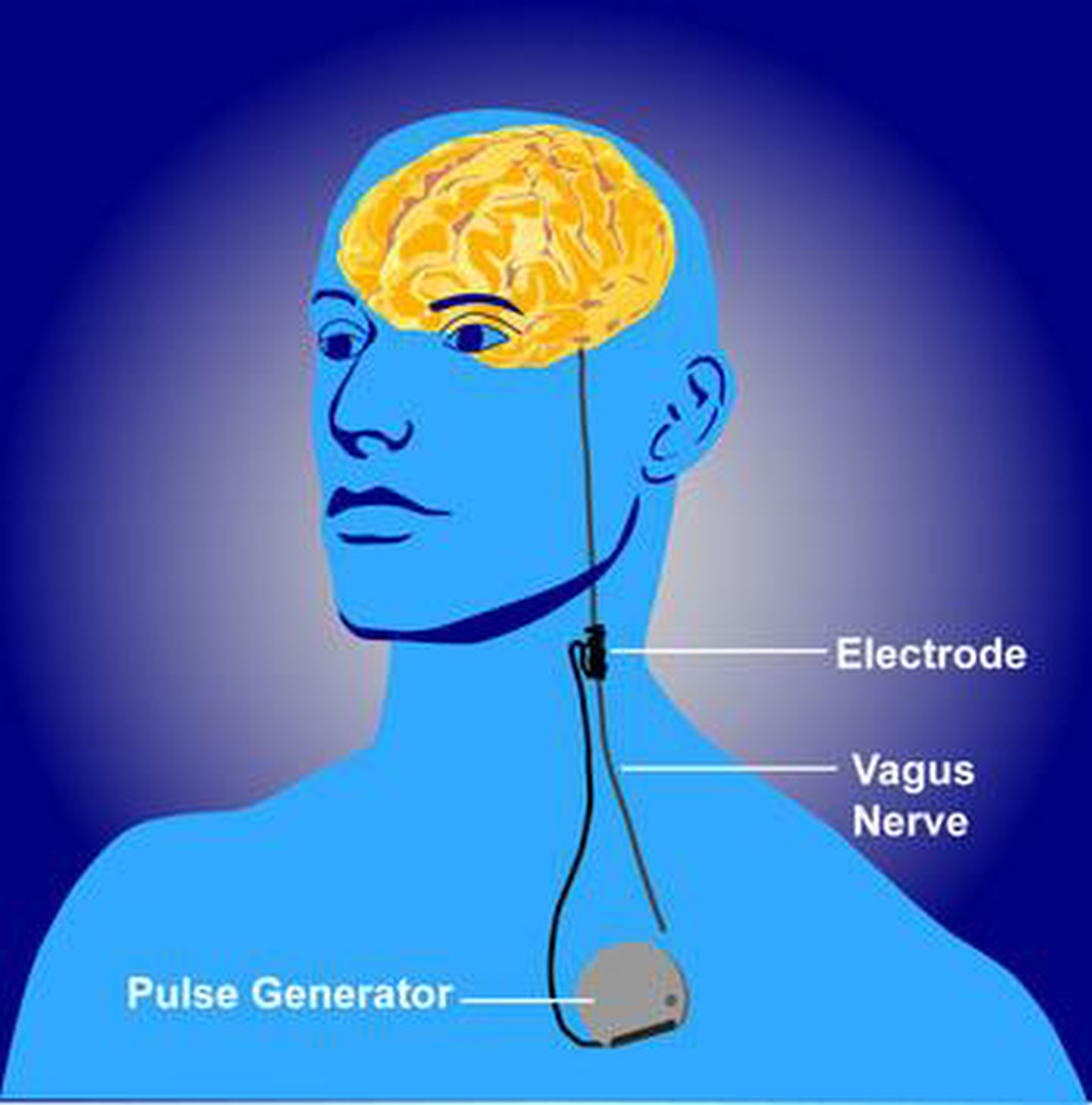

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) works through a device implanted under the skin that sends electrical pulses through the left vagus nerve, half of a prominent pair of nerves that run from the brainstem through the neck and down to each side of the chest and abdomen. The vagus nerves carry messages from the brain to the body's major organs, like the heart, lungs and intestines, and to areas of the brain that control mood, sleep, and other functions.

VNS was originally developed as a treatment for epilepsy. However, it became evident that it also had effects on mood, especially depressive symptoms. Using brain scans, scientists found that the device affected areas of the brain that are also involved in mood regulation. The pulses also appeared to alter certain neurotransmitters (brain chemicals) associated with mood, including serotonin, norepinephrine, GABA and glutamate. (5)

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved VNS for use in treating major depression in certain circumstances—if the illness has lasted two years or more, if it is severe or recurrent, and if the depression has not eased after trying at least four other treatments. Despite FDA approval, VNS remains a controversial treatment for depression because results of studies testing its effectiveness in treating major depression have been mixed.

How does it work?

A device called a pulse generator, about the size of a stopwatch, is surgically implanted in the upper left side of the chest. Connected to the pulse generator is a lead wire, which is guided under the skin up to the neck where it is attached to the left-side vagus nerve.

Typically, electrical pulses that last about 30 seconds are sent about every five minutes from the generator to the vagus nerve. The duration and frequency of the pulses may vary depending on how the generator is programmed. The vagus nerve, in turn, delivers those signals to the brain. The pulse generator, which operates continuously, is powered by a battery that lasts around 10 years, after which it must be replaced. Normally, a person does not feel any sensation in the body as the device works, but it may cause coughing or the voice may become hoarse while the nerve is being stimulated.

The device also can be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over the chest where the pulse generator is implanted. A person may want to deactivate it if side effects become intolerable or before engaging in strenuous activity or exercise because it may interfere with breathing. The device reactivates when the magnet is removed.

What are the side effects?

VNS is not without risk. There may be complications, such as infection, from the implant surgery, or the device may come loose, move around or malfunction, which may require additional surgery to correct. Long-term side effects are unknown.

Other potential side effects include:

Voice changes or hoarseness

Cough or sore throat

Neck pain

Discomfort or tingling in the area where the device is implanted

Breathing problems, especially during exercise

Difficulty swallowing

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation [rTMS]

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation [rTMS]

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) uses a magnet instead of an electrical current to activate the brain. First developed in 1985, rTMS has been studied as a possible treatment for depression, psychosis and other disorders since the mid-1990's.

Clinical trials studying the effectiveness of rTMS reveal mixed results. When compared to a placebo or inactive (sham) treatment, some studies have found that rTMS is more effective in treating patients with major depression. (6) But other studies have found no difference in response compared to inactive treatment. (7)

In October 2008, rTMS was approved for use by the FDA as a treatment for major depression for patients who have not responded to at least one antidepressant medication. It is also used in countries such as in Canada and Israel as a treatment for depression for patients who have not responded to medications and who might otherwise be considered for ECT.

How does it work?

Unlike ECT, in which electrical stimulation is more generalized, rTMS can be targeted to a specific site in the brain. Scientists believe that focusing on a specific spot in the brain reduces the chance for the type of side effects that are associated with ECT. But opinions vary as to what spot is best.

A typical rTMS session lasts 30 to 60 minutes and does not require anesthesia. An electromagnetic coil is held against the forehead near an area of the brain that is thought to be involved in mood regulation. Then, short, electromagnetic pulses are administered through the coil. The magnetic pulse easily passes through the skull and causes small electrical currents that stimulate nerve cells in the targeted brain region. And because this type of pulse generally does not reach further than two inches into the brain, scientists can select which parts of the brain will be affected and which will not be. The magnetic field is about the same strength as that of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Generally, the person will feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head as the pulses are administered.

Not all scientists agree on the best way to position the magnet on the patient's head or give the electromagnetic pulses. They also do not yet know if rTMS works best when given as a single treatment or combined with medication. More research, including a large NIMH-funded trial, is underway to determine the safest and most effective use of rTMS.

What are the side effects?

Sometimes a person may have discomfort at the site on the head where the magnet is placed. The muscles of the scalp, jaw or face may contract or tingle during the procedure. Mild headache or brief lightheadedness may result. It is also possible that the procedure could cause a seizure, although documented incidences of this are uncommon. A recent, large-scale study on the safety of rTMS found that most side effects, such as headaches or scalp discomfort, were mild or moderate and no seizures occurred. (8) Because the treatment is new, however, long-term side effects are unknown.

Magnetic Seizure Therapy

Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) borrows certain aspects from both ECT and rTMS. Like rTMS, it uses a magnetic pulse instead of electricity to stimulate a precise target in the brain. However, unlike rTMS, MST aims to induce a seizure like ECT. So the pulse is given at a higher frequency than that used in rTMS. Therefore, like ECT, the patient must be anesthetized and given a muscle relaxant to prevent movement. The goal of MST is to retain the effectiveness of ECT while reducing the cognitive side effects usually associated with it.

MST is currently in the early stages of testing, but initial results are promising. Studies on both animals and humans have found that MST produces fewer memory side effects, shorter seizures, and allows for a shorter recovery time than ECT. (9, 10) However, its effect on treatment-resistant depression is not yet established. Studies are underway to determine its antidepressant effects.

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) was first developed as a treatment for Parkinson's disease to reduce tremor, stiffness, walking problems and uncontrollable movements. In DBS, a pair of electrodes is implanted in the brain and controlled by a generator that is implanted in the chest. Stimulation is continuous, and its frequency and level is customized to the individual.

DBS has only recently been studied as a treatment for depression or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Currently, it is available on an experimental basis only. So far, very little research has been conducted to test DBS for depression treatment, but the few studies that have been conducted show that the treatment may be promising. One small trial involving people with severe, treatment-resistant depression found that four out of six participants showed marked improvement in their symptoms either immediately after the procedure, or soon after. (11) Another study involving 10 people with OCD found continued improvement among the majority three years after the surgery. (12)

How does it work?

DBS requires brain surgery. The head is shaved and then attached with screws to a sturdy frame that prevents the head from moving during the surgery. Scans of the head and brain using MRI are taken. The surgeon uses these images as guides during the surgery. Patients are awake during the procedure to provide the surgeon with feedback, but they feel no pain because the head is numbed with a local anesthetic.

Once ready for surgery, two holes are drilled into the head. From there, the surgeon threads a slender tube down into the brain to place electrodes on each side of a specific part of the brain. In the case of depression, the part of the brain targeted is called Area 25. This area has been found to be overactive in depression and other mood disorders. (11) In the case of OCD, the electrodes are placed in a different part of the brain believed to be associated with the disorder.

After the electrodes are implanted and the patient provides feedback about the placement of the electrodes, the patient is put under general anesthesia. The electrodes are then attached to wires that are run inside the body from the head down to the chest, where a pair of battery-operated generators are implanted. From here, electrical pulses are continuously delivered over the wires to the electrodes in the brain. Although it is unclear exactly how the device works to reduce depression or OCD, scientists believe that the pulses help to "reset" the area of the brain that is malfunctioning so that it works normally again.

What are the side effects?

DBS carries risks associated with any type of brain surgery. For example, the procedure may lead to:

Bleeding in the brain or stroke

Infection

Disorientation or confusion

Unwanted mood changes

Movement disorders

Lightheadedness

Trouble sleeping

Because the procedure is still experimental, other side effects that are not yet identified may be possible. Long-term benefits and side effects are unknown.

Resources

Brain Stimulation

Brain Stimulation aims to be the premier journal for publication of original research in the field of neuromodulation. The journal includes: a) original articles (up to 4,000 words); b) brief reports (up to 1,000 words); c) invited and original reviews; d) technology and methodological perspectives (reviews of new devices, description of new methods, etc.); and e) letters to the Editor. Special issues of the journal will be considered based on scientific merit.

Mayo Clinic - Deep Brain Stimulation

Overview - Deep brain stimulation involves implanting electrodes within certain areas of your brain. These electrodes produce electrical impulses that regulate abnormal impulses. Or the electrical impulses can affect certain cells and chemicals within the brain. The amount of stimulation in deep brain stimulation is controlled by a pacemaker-like device placed under the skin in your upper chest. A wire that travels under your skin connects this device to the electrodes in your brain.

Psychology Today - Brain Stimulation Therapy

Brain stimulation therapy is a procedure that uses electrodes or magnets in the brain or on the scalp to treat some serious mental disorders that do not respond successfully to commonly used psychotherapies and medications. There are several types of brain stimulation therapies, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), magnetic seizure therapy (MST), and deep brain stimulation (DBS).

Of these, ECT is the oldest and most widely used procedure. The other brain stimulation therapies are interventions that are sometimes used to treat other medical conditions, or they are newly developed therapies, but more research needs to be done to determine their effectiveness and safety in treating mental disorders.

What research is underway on brain stimulation therapies?

Brain stimulation therapies hold promise for treating certain mental disorders that do not respond to more conventional treatments. Therefore, they are of high interest and are the subject of many studies. For example, researchers continue to look for ways to reduce the side effects of ECT while retaining the benefits. Studies on rTMS are ongoing and include a trial in which the procedure is being tested for safety and effectiveness for the treatment of major depression in 240 participants. Similar studies are being conducted using MST.

Other researchers are studying how the brain responds to VNS by using imaging techniques, such as PET scans. Finally, although DBS as a depression treatment is still very new, researchers are beginning to conduct studies with people to determine its effectiveness and safety in treating depression, OCD and other mental disorders.

Citations

1 Kellner CH, Knapp RG, Petrides G, Rummans TA, Husain MM, Rasmussen K, Mueller M, Berstein HJ, O-Connor K, Smith G, Biggs M, Bailine SH, Malur C, Yim E, McClintock S, Sampson S, Fink M. Continuation electroconvulsive therapy vs pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in major depression: a multisite study from CORE. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;63(12):1337-1344.

2 Fink M, Taylor MA. Electroconvulsive therapy. Evidence and challenges. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007 Jul 18; 298(3): 330-332.

3 Dukakis K, Tye L. Shock: The healing power of electroconvulsive therapy. New York: Avery, 2006.

4 Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Fuller R, Keilp J, Lavori PW, Olfson M. The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 Jan;32(1): 244-254.

5 George MS, Sackeim HA, Rush AH, Marangell LB, Nahas Z, Husain MM, Lisanby S, Burt T, Goldman J, Ballenger JC. Vagus nerve stimulation: a new tool for brain research and therapy. Biological Psychiatry. 2000 Feb 15;47(4):287-295.

6 Fitzgerald PB, Brown TL, Marston NA, Daskalakis ZJ, De Castella A, Kulkarni J. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;60(10):1002-1008.

7 Loo CK, Mitchell PB, Croker VM, Malhi GS, Wen W, Gandevia SC, Sachdev PS. Double-blind controlled investigation of bilateral prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of resistant major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2003 Jan;33(1):33-40.

8 Janicak PG, O-Reardon JP, Sampson SM, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, Rado JT, Heart KL, Demitrack MA. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a comprehensive summary of safety experience from acute exposure, extended exposure, and during reintroduction treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;69(2):222-232.

9 Lisanby SH, Luber B, Schaepfer TE, Sackeim HA. Safety and feasibility of magnetic seizure therapy (MST) in major depression: randomized within-subject comparison with electroconvulsive therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003 Oct; 28(10):1852-1865.

10 Spellman T, McClintock SM, Terrace H, Luber B, Husain MM, Lisanby SH. Differential effects of high-dose magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive shock on cognitive function. Biological Psychiatry.2008 Jun 15;63(12):1163-1170.

11 Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, McNeely HE, Seminowicz D, Hamani C, Schwalb JM, Kennedy SH. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005 Mar 3; 45(5):651-660.

12 Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, Rezai AR, Kubu CS, Malloy PF, Salloway SP, Okun MS, Goodman WK, Rasmussen SA. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Nov; 31(11):2384-2393.

![Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation [rTMS]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5622dde8e4b021dd85232283/1551812072458-UB5GMHA2MB6AZ4ABP0N6/Repetitive+transcranial+magnetic+stimulation.png)